イベント詳細

シリーズ PRIDE(ナンバーシリーズ)

主催 DSE

開催年月日 2002年11月24日

開催地 日本

東京都文京区

会場 東京ドーム

開始時刻 午後5時

試合数 全9試合

放送局 フジテレビ(地上波)

入場者数 52,228人

シリーズ PRIDE(ナンバーシリーズ)

主催 DSE

開催年月日 2002年11月24日

開催地 日本

東京都文京区

会場 東京ドーム

開始時刻 午後5時

試合数 全9試合

放送局 フジテレビ(地上波)

入場者数 52,228人

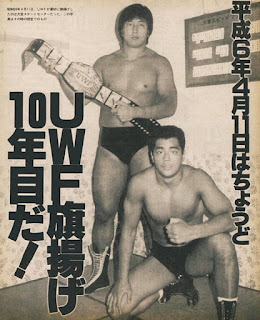

"It's not part of the UWF, but I can see the shadow, the ghost of the UWF in it." These words, spoken by 斎藤 文彦 Fumihiko Saitо̄ to Justin Knipper in a not-that-recent episode of their often excellent Write That Down! podcast (its title taken from Chris Jericho's Fumi-Saitо̄wards NJPW-press-conference exhortations), speak to to the very core of our efforts here. Their subject, in that particular moment, was the famous 1/4/99 東京ドーム Tōkyō Dōmu contest between 小川 直也 Ogawa Naoya (known well to us in these pages) and 橋本 真也 Hashimoto Shin'ya (largely unmentioned heretofore) that escalated (or descended, I suppose) from a worked NJPW professional wrestling match into a disordered (乱 ran) InokiIST shoot-fracas of some kind. Throughout their really quite remarkable three-episode series on the subject (the UWF I mean), Fumi Saitо̄ examines "[w]hat UWF was, or, as a whole, what we know as professional wrestling: where it is from, the way it is now, and where it's going in the future. Really, that big." He argues (compellingly!) that we can't begin in 1984, with the formation of the first UWF proper, but rather we need to look to Inoki's 1972 formation of 新日本プロレスリング株式会社 / Shin Nihon Puroresuringu Kabushiki-gaisha / New Japan Pro-Wrestling (an "outlaw promotion," Fumi asks us to imagine, or remember; Inoki's second such venture [but the one that took]) under the extraordinary influence of Karl Gotch (about whom Fumi made an intermittently watchable thirty-minute documentary in 1992); he asks us to consider the emergence of Inoki's "strong style" as a deliberate departure from either the "King's Road" or American "showman" styles that preceded it (that Fumi specifically uses these ファイヤープロ オーディエンスマッチ / Fire Pro Audience Match names obviously delights me [Fumi's Fire Pro bone fides {or firepronefides} are, of course, as bona fide as can be]). There are so many things that I would like to share with you from these three wonderful episodes! I listened to them all once-through whilst doing chores (among the purest forms of podcast enjoyment, I think, chores-listening), and then listened again another time to take notes, which, although it was not my intention while I was writing them down, I might as well just post here in their entirety, like so (please forgive any transcription errors; if anything does not make sense, assume the fault is mine, and not Fumi's):

—"What UWF was, or, as a whole, what we know as professional wrestling, where it is from, the way it is now, and where it's going in the future. Really, that big."

—We need to begin in 1972. Inoki's formation of NJPW. The extraordinary influence of Karl Gotch (made a movie about him in the 1990s, Kami-sama). Strong style, as opposed to the existing king's road style, or the American style / showman style (Fire Pro verbiage). This offers us "theme and anti-theme, thesis and antithesis."

—The UWF style truly changed from strong style to shoot style (a stronger style still, as we have said a bunch, since our beginning) specifically at the end of the first UWF tour in 1984, two consecutive nights at Korakuen Hall. "They became what we call 打投極 datо̄kyoku. 'Da' / 打 means striking. 'Tо̄' / 投 means "nageru," throwing, suplexing. 'Kyoku' / 極 meaning submission. Striking, and suplexing, and submissions. Oh my gosh: that sounds like MMA twenty years later, right?" [投 / nageru comes up kind of a lot in our judo kanji, as you might expect! I admit to being perplexed by the last bit, though, in that the "kyoku" that makes the most sense to me here is 決, rather than 極, but the only compound "datoukyoku" I am able to find for this specific usage is indeed 打投極 and so I of course defer to that formation utterly because what on earth do I know {so very little}, but if any of you can speak to this please let me know! I am very easily confused {also startled}]

—"To make wrestling into legitimate contest was the whole idea. It was still pro wrestling, I believe, yeah. And they will never admit to it, you know, because they were making professional wrestling their idea of professional wrestling." No running the ropes. No dropkicks. No fighting outside the ring. Winners and losers. "It's a 1980s interpretation, but what they were doing is what Frank Gotch was doing in 1900s, don't you think? What the UWF was doing in the late 80s, it was like going back about a century, you know? That's why it's so fascinating, you know. And that's what Inoki wanted in the first place!" [Shoot style not as strong style at its end, but in its nascent state, and this state is constant? Was Jean-François Lyotard not just right about postmodernism, but shoot style, too? It wouldn't surprise me!]

—it felt like "a political movement"

—the rise of Japanese vs Japanese main events (as opposed to Japanese vs. foreigner)

—On dealing with the press: "UWF guys were pretty open, nothing to hide kind of guys; they were pretty friendly back then" unlike the NJPW guys, who would sometimes be "angry" to see reporters backstage. Fumi specifically mentions a young lion Chris Benoit as being angry in this way. Print media was enormous then, and Maeda, Takada, Fujiwara, Sayama were all eager to talk with the press (had not been nearly as free to do so under Inoki). Instead of dealing with NJPW public relations people, you would just spend an afternoon at the UWF dojo. [see also: Write That Down! episode "Pro Wrestling and Print Media"]

—UWF never had tv in any of its incarnations, but the second UWF coincided with the peak of VHS (every show taped and released; some would sell 100k)

—the original NJPW offer to Akira Maeda was for him to join the NJPW dojo straight out of high school, and they would send him on excursion to New York to open a karate school! What! "Inoki is like a father figure, but also someone Maeda really has to walk away from to be himself."

—"Gracie became famous by fighting pro wrestlers. Royce Gracie vs. Ken Shamrock made UFC famous, right?" And Rickson, Justin Knipper ably prompts. "That too. Always fighting wrestlers. Not MMA fighter. But the Gracie against pro wrestler, that was so exciting. But it wasn't Takada, you had to wait for the rise of Sakuraba." [Consider again Tadashi Tanaka's letter to the 8/2/99 Observer {reproduced here}: "The original UWF movement to turn the fantasy of pro wrestling into reality was accomplished this year." Takada as middle brother between eras: "the pain put on the middle brother was beyond the imagination." We really should revisit the whole letter again soon: "pro wrestling proved to be a real martial art and Takada proved it by committing suicide."]

—"Naoya Ogawa was almost like an alien coming to the scene. Inoki put him in the ring with zero training in professional wrestling; just go out and do it." [As we have long noted in the context of RINGS specifically: excellent shoot-style work often emerges out of the athletes with the least "pro wrestling" training, rather than the most {Bryan Alvarez has made this point too, comparing the frequent excellence of minimal-training shoot style vs. the inescapable disaster of minimal training lucha libre}; consider too our enthusiasm for the Frank Mir / Dan Severn Bloodsport match vs. the general antipathy with which it was met]

—"That was the beginning of our dark age, and I almost gave up on it once." (the UWF's culmination in PRIDE; the pummeling of and sharp decline in "traditional," non-UWF pro-wrestlers and pro-wrestling)

-- "UWF is a big theme, and is almost like a big project to understand, because it is so influential. It might be the biggest thing in the 80s and 90s that happened in Japanese wrestling."

—Inoki was influenced by all of this as well, Knipper observes. "Or," Fumi counters, "he was the one who influenced it!"

—Inoki wanted to make an Inoki out of Ogawa. "It's not part of the UWF," Fumi Saito says of Ogawa/Hashimoto, "but I can see the shadow, the ghost of the UWF in it."

—"A lot of UWF fans went to MMA and never came back [to traditional pro wrestling]." In the Japanese context, nearly all of them then left MMA, too.

—"Inoki sided with these people at the time." He sold NJPW. And seemed to have decided "entire MMA genre could be his." And then when Inoki started UFO (Universal Fighting-Arts Organization, and later IGF, Inoki Genome Federation), with Ogawa as its star and Sayama as its head trainer, Fumi didn't know if it was best understood as a pro wrestling promotion or an MMA company.

— The New Year's Eve era. Pride on channel 6, K-1 on channel 8, Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye on channel 4. This era, to Fumi: "That was my darkest day of pro wrestling. It became 100% MMA. And worse yet," traditional pro wrestlers like Nagata and Kashin fought and lost, often badly. Sakuraba does not come up quite as much as you might think in this whole conversation (not that he is, in Saito's formulation, a "traditional" pro wrestler [despite his love of Tiger Mask, etc.], but instead a figure of the UWF).

—On the Gracies: "You can't deny the fact that they became famous by involving pro wrestling." "Wasn't jūjutsu used to be self defense? [It] wasn't a business to make money, and then franchise your dōjō all over the world, and sell your merchandise. But it became business. Big business. Now every shopping mall in your block in America you have a little bit of jiu-jitsu dojo in your neighbourhood."

—"Dōjō became English word, too. That's good!"

—"I actually interviewed Rickson Gracie couple times in Japan. He was very much like the real martial arts master, and I believed him. He's very sincere. Some people say Rickson, like the entire Gracie family, such a businessman, and they only do their fight [according to their own rules, etcetera—ed.], and they love money, money making ventures, and all these things. Uh uh uh. I think he was a lot like Karl Gotch. It was their family that was doing business, but Rickson Gracie himself wasn't a power monger, or money lover, or businessman-type-deal. He really, really was like a martial arts dojo sensei type. I met him. And I sat down couple hours, and, just, he was not like professional wrestler interview who kayfabes everything. No, he was like philosopher. Trust me." [I kind of do, actually, on account of how, despite all the mythology and silliness, which should probably overwhelm any other consideration, I have a warm personal recollection of how Rickson Gracie was nice to me and my friends when he walked over to shake our hands, and how he led a good, solid, grounded class that I was grateful to have been invited to. It made for a nice afternoon!]

For anyone inclined towards any of what we've done here in the last I suppose eight years (which feels about right, actually), I really can't recommend these episodes enough. And when you're through those, you'll no doubt want to spend eight hours or so with the five-part series on Antonio Inoki (the first part is here). I must say that in addition to his deep knowledge of these subjects, I just find Fumi Saitō a pleasant person to be around in manner and disposition (and also part-time university instructors need to stick together [solidarity]). The congenial-too Justin Knipper strikes a great balance between moving things along and giving Fumi enough room to really air it out sometimes. Also, I find myself at a point in my study of the Japanese language where I am disinclined to actively seek out takes on these matters from people who do not have the capacity to contend with the primary texts beyond my own ability, and on this score, the podcast triumphs once again, as Knipper is a fluent Japanese speaker; this does not come up directly in the podcast all that often, but when it does, it feels important, and it certainly cannot help but inform the whole exercise. All good stuff!

Anyway! What show was it that we were going to watch together today in fellowship and maybe even joy?

OH YES THAT'S RIGHT IT IS PRIDE.23(プライド・トゥウェンティスリー)2002年11月24日 BEFORE A CROWD OF 52,228人 (though I suppose that 人-number may come down a little on appeal [when we read the Observer]) AT NO LESS A VENUE THAN THE 東京ドーム TО̄KYО̄ DО̄MU ITSELF and in fact it is the precise nature of this particular event that led me to think it would be an appropriate occasion upon which (excuse me: uponst which) to mention the Fumi Saitō/Justin Knipper UWF series, in that, although surely everything that occurs in these pages speaks in one way or another to The Long UWF (as it has come to be known [to us {and also to like maybe three other guys}]), PRIDE.23 is one where you do not need a map, folks; this is as "Long UWF" as it gets (soon enough we will see why!). I am pretty sure I have not watched this show in its entirety in the better part of twenty years, and let me tell you I am super stoked so to do (seems meet, seems right).

No sooner do we open pride.fc.23.championship.chaos.2.dvdrip.xvid.cd1-kyr (so fine and fair a file) than we are met with Stephen Quadros and Bas Rutten, who are lightly engaged in an opening skit regarding off-track betting. It's not great, but they don't lean especially hard into it, so no harm is done. As we cut quickly to the parade of fighters, it is remarkable how highly crowd-esteemed pretty much all of these guys are (as they, you know, parade), a reminder that we are at-or-near the peak of all this: this is an enormous crowd, and these athletes are "over" before it. As far as sartorial choices go, the clear winners are Фёдор Влади́мирович Емелья́ненко / Fyodor Vladimirovich Yemelyanenko / Fedor Vladimirovich Emelianenko in a tracksuit, and Don Frye in a 稽古着 / けいこぎ/ keikogi, and when I say it like that it occurs to me I may just be choosing these two looks as the top ones because, together, they comprise the only things I have worn to the gym in really quite a long while (compression shirt and leggings beneath both, naturally). As you can see below, though, that those highly localized effects aside, they really are strong looks, bordering, indeed, on lewks:

I mean, come on.

Our opening contest features neither of those problematic faves, but instead Dutch kickboxer Jerrel Venetiaan, who makes the super aggressive and perhaps unprecedented decision to stand in the corner of his opponent 横井宏考 Yokoi Hirotaka during the introductions, while Yokoi's second, no less stalwart a figure than 高阪 剛 Kōsaka Tsuyoshi himself (as we gather here beneath the auspices of his scissors), looks on nonplussed (in the original sense of bewildered and unsure). It's pretty weird!

This postural bluster (blusteral posture?) collapses as soon as the bout actually begins, as Yokoi tackles Venetiaan down immediately (an objective truth) and effortlessly (easy for me to say) with the 手技 / te-waza / hand technique of 双手刈 / morote-gari, the two-handed reap (back to objective truth). This conforms to what we know of Yokoi, of whom we spoke as recently as QUINTET (クインテット) 2019年2月3日: FIGHT NIGHT2 in TOKYO (oh man that was five years ago!), when he competed on behalf of Team U-Japan (hey I wonder what that "U" refers to? [haha no I don't!]) against team NEO-JUDO. And yet Yokoi could himself well have been a Neo-Judoist! As Wikipedia tells us, "Yokoi originally started training in Judo in high school, but he was more interested in Universal Wrestling Federation and its offshoots. He participated at a Shooto mixed martial arts tournament during his stay at the Kinki University, and later moved to Fighting Network RINGS." All true! I wonder how his QUINTET match went . . . let's see what we had to say at the time:

"Koshi Matsumoto (77.45 kg) is the Neo Judoist who will face Hirotaka Yokoi (99.40 kg), the final member of Team U-Japan, with Yokoi needing to finish a submission in but four minutes (he is large and so their match is short). Yokoi we know from RINGS! He had eight matches there in the latter, largely-shoot era of it, and then lost a bunch in PRIDE but did well, if I recall correctly, against Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira, which is a kind of victory. Koshi Matsumoto is unknown to me but it seems his judo has taken him to SHOOTO extensively, to Pancrase a little, and RIZIN most recently. True to his Fighting Network RINGS roots, Hirotaka Yokoi, when knee-barred, immediately grabs a toe-hold rather than work for an escape; he has entered shoot leg-lock duel and I salute him for this tribute to the era of Akira Maeda and Volk Han and other friends from there, from then. Stewart Fulton, though sometimes lightly corny when he tries to shoehorn in un bon mot, has excellent technical knowledge and is clearly very well-prepared to discuss each athlete's background, and is doing a very good job. Yamamoto does not seem particularly inclined to join in, really, and she even apologizes for her inability to really keep up with the pace of the matches (this may well just be modesty, but either way, she's not talking), so he's working almost solo, and it can't be easy. The match ends in a draw and so NEO JUDO DESU is the non-Lenne-Hardt ring announcer's call. That was all extremely pleasant."

I am very pleased to have had this opportunity to be reminded of just how neat this show was. I mean, look at this:

This may have never quite happened to you before, but let me tell you, it is absolutely staggering to be catered to with such razor-sharp precision, and in such sikk fashion. In their pre-taped promos that night, judo 四段 yondan Tsuyoshi Kohsaka, said, "There's no doubt that UWF is what set me on the path to fight in MMA. The U of UWF is in my blood. It's in my DNA. Everyone of my moves comes from UWF," to which 小見川道大 Omigawa Michihiro countered, "TEAM NEO JUDO is here and we're all judoka. We are five men who put all our faith in judo. We're going to show what judo can do and we'll win doing it." Unreal. Just unreal.

From 2019, let us return not to the 2024 of our present encounter so much as the 2002 of our present material, and note that Yokoi had no trouble at all, really, with the game-but-newaza-untutored Venetiaan, finishing early in the second round the 腕挫十字固 ude-hishigi-juji-gatame that narrowly eluded him at the first round's close. Although this opening bout was not especially competitive, I liked it just fine: Yokoi's super correct smothering approach, no doubt borne of his super correct fear that an unsmothered Venetiaan would hit him just so hard, was active and interesting. "He kind of used the gentle art of submission to make the other guy quit," Quadros explains. They don't (which is to say, he doesn't) call him(self) "The Fight Professor" for nothing, folks! "Yep," Bas confirms. "And he does it beautiful!" All true! Yokoi's reward is that TK scoops him right up in a nice hug.

Hey look, next up it's UWF/KINGDOM/RINGS-guy 山本 喧一 Yamamoto Ken'ichi, and he's here to have a match against Kevin Randleman! This doesn't sound like a great idea, in that Yamamoto is really quite a bit smaller, and also really quite a bit not as good. Stranger things have happened though, and Randleman sometimes loses ones you'd never expect, so who can say? The first round unfolds not dissimilarly to our previous bout, in that it involves a great deal of "laying atop of": Randleman attacks throughout with 腕緘 ude-garami, sometimes twisting it fairly grossly, but Yamamoto is a calm guy, and bears it well. "There's Yoji Anjoh," Quadros notes between rounds, "from the old UWF days." You can see him peaking through betwixt the ropes here:

Yamamoto is a pretty cool customer, and Randleman seems fond of him. This does not, of course, preclude Randleman ending the fight with the highest grounded-knees anyone has ever seen, or indeed could ever see, like so:

A ruinous situation if you are 山本 喧一 Yamamoto Ken'ichi's head, or someone to whom 山本 喧一 Yamamoto Ken'ichi's head is important, either physically or emotionally.

BRAZILIAN TOP TEAM VS. CHUTE BOXE is on offer in this next bout between Ricardo Arona and Murilo Rua, aka NINJA (not to be confused with Mauricio Rua aka SHOGUN). You may well recall (it is totally fine if you don't; please don't worry) that when last we saw this particular Rua, he took a decision win over BTT's Mario Sperry at PRIDE.20(プライド・トゥウェンティ). Much is made here of the rivalry between these two strong teams, whose approach to fighting places differing emphases on the relative importance of hitting (Chute Boxe) versus smooshing (Brazilian Top Team), though there is broad agreement between them that both are of value. With so much common ground it seems silly to argue at the margins, but these young men in their twenties, some of whom possess improbably powerful builds (for whatever reason! who can say!), are not in a place in their lives where they are yet able to share this assessment, and that's fine too. I would remind the group that both fighters were, at the time of this encounter, among the finest in the world in their weight class, each with just one loss on their record (and to excellent competition: Arona to Fedor [you will recall, perhaps, RINGS], Rua to Dan Henderson [hey Henderson was in RINGS, too!]). Rua opens with a pretty spectacular flying knee, which seems more like the approach of a bold samurai rather than a sneaky ninja but I am not here to police sobriquets. It connects, this flying knee, though imperfectly, which allows Arona to take Rua to the mat pretty much right away, and although Rua pops right back up, it is not long at all before Arona has him on the mat again after an impressively clean 小外掛 / kosoto-gake (minor outer hook). If I am remembering Ricardo Arona's 立ち技 / tachi-waza (standing techniques) correctly—and I don't mean to brag or boast unduly here guys when I say that I am pretty sure I do—the minor outer hook of kouchi-gake remains his 得意技 / tokui-waza (let's go with "preferred technique" on this one) throughout his fine career. That Arona is the superior grappler is no surprise, but Rua is no slouch, and intrigues me pretty hard with an 腕挫腕固 / ude-hishigi-ude-gatame ("straight armlock," let's say, rather than the literal "arm breaking arm lock," which, out of context [and also I suppose in context] could be just about any of them) off his back that comes nowhere near finishing, but which generates 崩 / kuzushi (unbalancing), and so forces Arona to respond. "I got an adrenaline rush right going on here" is Bas Rutten's idiosyncratic but spot-on analysis. A scramble that exposes, in time, both fighters' backs, also exposes Rua's new tattoo, about which Bas is curious:

ムリーロ・ニンジャ is "Murilo Ninja" in katakana, the script reserved for foreign/loan-words, and it is interesting that he went with ニンジャ for "ninja" instead of 忍者 but I guess it's probably the right call unless you wanted people to have to ask if you pronounce it "ninja" (the on'yomi) or "shinobi" (the kun'yomi), as both are viable readings of the same kanji (what a language!). Could maybe be a good conversation starter that way though? I don't know that Murilo Rua struggled to meet people (though of course many do; a priest I once knew would ask that we hold the lonely in our prayers). Back to their feet, striking a little, clinching only to be separated quickly: that's the kind of thing we are into for the next little while. When Arona takes Rua down the next time, it's not even really with an identifiable attack, just a waist-lock and a little push (you get low, Arona's cornerman Mario Sperry has VHS-told us before and will tell us again, and you pooooooosh). Arona throws grapple-caution to the wind to attack with the naked strangle (though they are all naked strangles without the 道着 / dо̄gi [stop me if I have made this point before]) of 裸絞 / hadaka-jime, and it lightly costs him, as Rua turns out of the attack (in the "back-to-the-mat" direction of hadaka-jime escape, rather than the "finish-the-seoi-direction," which I honestly prefer! [but then I am a seoi guy; I am a seoi guy]) and ends up on top for a good long time after. Eventually the fight is restarted standing, and Arona is offered the caution and guidance of 指導 shidо̄ for his overly defensive guard play; Stephen Quadros feels that this is perhaps a little harsh, but Arona is actually being so defensive here that I was reflecting on how well he is enacting the principle of 引き込む / hikikomu (drawing in), which is likely sign that a stand-up is right around the corner (turns out it was!). During this period of relative inactivity, Quadros addresses the idea that mixed fighting in America and mixed fighting in Japan are really very different experiences because of several key discrepancies in the rules and judging, but he raises this notion only to dismiss it (the technique is refutatio), ultimately arguing that "there are more similarities than there are differences," which is no doubt true: fundamentally, a mixed fight is still a mixed fight, as opposed to, say, a dinner with an army buddy who brings along an attractive daughter (a Kids in the Hall reference to a sketch I can't find to link to! the internet has never truly done right by that important series), or anything of the sort. As the first round draws to a close, it is again Arona's 小外掛 kosoto-gake that puts Rua where he wants him (or at least where he prefers him); a final-seconds 片足挫 kata-ashi-hishigi / single-leg-crush / Achilles lock doesn't really go anywhere, but it does cement the round, one would think, for Arona.

OH MY GOODNESS 払腰 HARAI-GOSHI TO OPEN ROUND TWO:

Great idea, Ricardo Arona! A truly dynamic technique that not only delights one and all, but positions Arona perfectly to pursue his true calling of laying on top of guys forever. For perhaps the first time, but certainly not the last (I remember it happening a lot), Stephen Quadros mentions Maurilo Rua's enthusiasm for the music of Lionel Richie, which I honestly don't find remarkable at all, but instead just normal ("Hello" is a crucial component of my 空オケ karaoke repertoire). I am surprised and impressed with Rua's ability to explode right here and return to his feet, but it isn't long before Arona attacks with a pretty tight 前裸締 / mae-hadaka-jime/ front-choke in the particular mode of the "arm-in guillotine," a technique that our commentators are still not entirely convinced of, like in the sense that they are still not of the view that this is a viable thing at all (literally no one today doubts it; it is a settled question). Though Quadros argues, and Bas concedes, that Arona's great big muscly arms make it conceivable that this could be a technique, they do not on the whole suggest this is a thing to pursue at all. This remains so weird to hear! It is for sure not a great move positionally if you do not manage to finish, and sure enough Rua escapes, and stays on top for the remainder of this second (five-minute, as opposed to the ten-minute first) round. Arona's takedown early in the third (a low, tackling 双手刈 morote-gari) though less æsthetic than the 払腰 harai-goshi we got pretty into a moment ago, is no less effective, in that it sets up further Arona-laying-atop-of. "It doesn't set the public imagination on fire," Stephen Quadros suggests, "just being on top of a guy," but this is quite simply where Stephen Quadros and I part company; I'm not upset about it, and do not hold it against him. Our commentators suggest that a draw may well be in order here, but this seems a radical interpretation of the text. Officially, and I think quite reasonably, Arona takes the unanimous decision in a closely-contested bout. Let us close this chapter with a picture of Brazilian Top Team coaching hardly:

"Fedor is a very good fighter himself too," are words uttered by Bas Rutten ahead of a heavywight-championship-eliminator bout between the aforementioned Фёдор Влади́мирович Емелья́ненко / Fyodor Vladimirovich Yemelyanenko / Fedor Vladimirovich Emelianenko (mentioned just afore) and the very fine Heath Herring, but Bas agrees with Stephen Quadros' prediction of a Herring win by decision. It is easy for us to look back at this sort of comment now as obvious folly, but was it obvious? Was it even folly? There was much to admire in Heath Herring, certainly, and it is not necessarily the case that either Quadros or Rutten had seen much of Fedor in the fleeting (though aren't they all?) final days of Fighting Network RINGS on WOWOW ("Wowow [Wauwau, pronounced {waɯwaɯ}, stylized in all-uppercase in Japanese] is a satellite broadcasting and premium satellite television station owned and operated by Wowow Inc. (株式会社WOWOW). Its headquarters are located on the 21st floor of the Akasaka Park Building in Akasaka, Minato, Tokyo.[1][2] Its broadcasting center is in Koto, Tokyo.[1][3]" [left unspoken here is how WOWOW becomes NONON in ファイヤープロレスリング Faiyā Puro Resuringu but that's probably okay]). This is not to suggest that our commentators have not done their homework: for instance, Bas discloses that earlier he asked Heath Herring if he likes to eat herring, and he does, and Bas thinks this is good, because it is a healthy food, and I am sitting in front of my computer nodding about it and wondering if I have any oily little tinned fishes that I could maybe toss into a Nongshim Kimchi Ramyun for lunch . . .

IN THE END IT WAS SARDINES (that I shared with the cats) AS HEATH HERRING IS SWARMED EARLY (so too the sardines) and he's in just huge, huge trouble immediately: Fedor catches hold of a Herring low-kick, and flicks his good-sized 受け uke to the mat with a motion that resembles 支釣込足 sasae-tsurikomi-ashi but seemed too easy to have even been that, somehow, and then he is just all over him, moving from 横四方固 yoko-shiho-gatame to 浮固 uki-gatame to 縦四方固 tate-shiho-gatame (all bad gatames! to be under!) with a sudden deftness that almost recalls (here I am, almost recalling it) the preternatural movements of 田村潔司 Tamura Kiyoshi (about whom more soon enough!) when he was not so much fighting for real as fake-fighting as real-ly as possible (more on that too!). This of course leads to Herring giving up his back as he attempts to turtle (that's one step away from standing!) and stand (that's just one step past turtling! I am really pleased with how a broader martial arts audience has come around on the turtle in recent years; it really is a crucial position, not just defensively but transitionally, and it was weirdly maligned for a while there) no wait I got ahead of myself in that Herring, rather than stand, elects to roll through for a 膝十字固 hiza-juji-gatame / knee-bar, which I agree is a rad thing to do in theory, but let's turn it over to Stephen Quadros with the call: "Fedor gets out. Fedor on top. A lot of scurrying there. Heath almost got out from under the bottom, but now he's on the bottom of this guy who's a judo champion." All, alas, true. (For more on Fedor's judo credentials, we may wish to revisit his first RINGS appearance at RINGS 9/5/00: BATTLE GENESIS VOL. 6, where we totally went into them [his final judo tournament of record was the Dutch Open Grand Prix Rotterdam contested 3/3/00 through 4/2/00; his first mixed fight came just a month later at RINGS Russia: Russia vs. Bulgaria, 5/21/00]). Bas notes that Herring was also on the bottom against Nogueira, but survived it; the fact that Bas could think these two situations are at all analogous tells you how little of Fedor we then knew.

While all of this interesting positional work is taking shape, Fedor is really cracking Herring at every opportunity, leaving him all cut up, clearly dazed, and hurt: as he tries to get out of the way of really any number of blows, Herring inadvertently rolls out of the ring, and is offered the caution and guidance of 指導 shido for so doing (he is lucky this movevement is not adjudged a round-ending RING OUT [don't laugh, it can happen]). The ringside doctors (I'm assuming they're doctors) take this opportunity to have a look at Herring's sliced up face, but, owing primarily to man's inhumanity to man, determine that the fight may continue (oh no). No sooner does it (the fight) so do (continue) than Fedor slips under Herring's 釣り手 tsurite (lifting hand) and, once having assumed the position known to many exponents of the Georgian grip (I am many exponents) as "Georgian B" (as opposed to "Georgian A," which Georgian poor Herring has just unwittingly become), and performs what is so often Georgian B's principal attack from this configuration, which is all to say that Heath Herring gets utterly bombed with 裏投 ura-nage:

This is, in my experience, just no fun at all for Georgian A, who would be having a much nicer time were they controlling Georgian B's posture, and attacking with 隅返 sumi-gaeshi, 大外刈 osoto-gari, 小内刈 kouchi-gari, 大内刈 ouchi-gari, 釣腰 tsuri-goshi, or a rolling 内股 uchi-mata against Georgian B's deep hips. There really are any number of excellent options for Georgian A! But if Georgian B keeps their hips in and head up, there's much for Georgian A to contend with, from a squared-off, chest-to-chest, tackling form of 小外掛 kosoto-gake, to powerful forward lifts like 移腰 utsuri-goshi and 手車 te-guruma / 掬投 sukui-nage or, worst of all by really just so much, 裏投 ura-nage. Ura-nage is of course a technique of great significance in The Long UWF, not least of which because of its prominence in the No Rope Martial Arts Match for the WWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship contested between Antonio Inoki (who else?) and Georgian Olympic Judo Champion (Munich 1972, -93kg) შოთა ჩოჩიშვილი / Shota Samsonovich Chochishvili at 89格闘衛星☆闘強導夢 / '89 Kakutō Eisei ☆ Tōkyōdōmu / BATTLE SATELLITE IN TOKYO DOME, the first of the who-can-say-how-many NJPW Tokyo Dome shows that would follow—a clip of these historically significant ura-nage is available here. In any event, please spare a thought for the hoisted Heath Herring. Spare a thought for Georgian A.

What follows, unsurprisingly, is more hitting, as Stephen Quadros attempts to come to terms with what we've just seen. "Suplexing Heath Herring! Unreal! He picked the big man up like he was nothing!" Quadros exclaims, and it's super exciting, no question, but I'm telling you: hips in, head up, get low, and dig; you would be amazed what you can accomplish against a Georgian A significantly bigger than you, let alone someone of roughly the same size (which is the Fedor/Herring situation before us). Herring, to both his credit and peril, is a super tough guy, which is making this all the more difficult: he keeps fighting through, or keeps attempting to fight through, these just awful, awful shots. Deeply impressed and lightly unsettled by Fedor's quickness, Quadros mentions that Fedor is a relatively small heavyweight at 6'1" and 227 lbs, and it occurs to me just how small a heavyweight that really is, in that of the three heavyweights we see most often at our club, the one who is clearly the smallest is like exactly that size, like maybe even down to the pound depending on the time of day, and the other two are quite a big bigger. Oh man oh dear oh no: Herring has an easy way out when Fedor takes his back and attacks with 裸絞 hadaka-jime across the face, not quite around the neck (which is honestly so much worse) but he doesn't take it! Herring just needs to subtly, almost imperceptibly lift his chin for an instant and he can end the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to, and just out of basic human sympathy you kind of hope that he does, but he fights out of it—twice, in fact!—and ends up on top, and actually throws a couple of decent knees before the round ends. It is a remarkable show of heart but one that, understandably, the doctors will not allow to continue into the second round. That is officially a TKO by doctor stoppage. I remembered this match being a one-sided affair, but this was much more uncomfortable to revisit than I'd expected.

Antônio Rodrigo Nogueira vs. Semmy Schilt! Absolutely! This sounds like a great idea! One is the best heavyweight submission fighter in mixed fighting, and the other is super tall! And also an excellent kickboxer and 芦原 会館 Ashihara Kaikan karate 六段 / sixth-degree black belt. So he's got that going for him, too. Although Nogueira is, of course, our PRIDE FC Heavyweight Champion, this is a non-title fight (a fairly preposterous thing, when you think about it) held in the interest of just, like, joy and merriment and so forth. Man, look how tall! Look! I mean, Nogueira's six-foot-three!

With these two important heavyweight contests now settled, one's thoughts cannot but turn towards the coming championship contest between Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira and Fedor Emelianenko, and about how extensively it will rule.

And now it's middleweight (in the sense of 205lbs) champion WANDERLEI SILVA defending that title against our dear old pal 金原弘光 Kanehara Hiromitsu, who Stephen Quadros refers to not just as Hiromitsu Kanehara, but "Hiromitsu Kanehara, from RINGS" (emphasis his [and of course also mine]). "You read me the list with the opponents that Kanehara was fighting," Bas says to his partner, "and this guy fought a lot of people, and he beat some good people, too, so he has a lot of talent, and he has a lot of experience. But, Wanderlei Silva; come on: 'The axe murderer' from Brazil? I don't know." I cannot help but agree with all of it. And if you'd wondered if Kanehara would show up in an oversized shirt all sliced up into a weird poncho with 高阪 剛 Kōsaka Tsuyoshi in his corner, wonder no more, friends:

I feel more than a little worried about what is obviously about to happen, but I need to remind myself that Kanehara seems to be doing okay these days (he posts sometimes and seems well; he is involved in health care, broadly conceived) so however horribly this goes (I do not remember it clearly), the effects were possibly not life-altering? The crowd sure loves this guy, and I join them in this so hard. Somewhat surprisingly, Kanehara comes out slugging; less surprisingly, so too Wanderlei. It is a left high-kick that puts Kanehara on his back just a few seconds in, but he has his wits about him enough to start tying up arms and working his hips towards an 腕挫十字固 ude-hishigi-juji-gatame, that, I am sorry to say, does not in fact seem super available at the moment. It's enough of a threat that Silva decides he would rather back out and have the fight return to standing, and as Kanehara hops up, ready for another go, the crowd is once more stoked. You'd think Silva's plan might be to just stand and box Kanehara up, but he actually lands a tidy 小外掛 kosoto-gake to return the fight to the mat soon thereafter. Silva smartly backs out and stands whenever he's anything less than perfectly content with the way things are going, and the result, in time, is a really quite a lot of soccer kicks (tricky to actually land!) and stomps (seemingly easier). Kanehara remains game—and, as a true man of RINGS, seems to think he can maybe just grab a leglock real quick here—but Tsuyoshi Kohsaka has seen enough, throws in the towel, and dashes in with a look of both concern and apologetic explanation about him. Kanehara seems surprised, and a little disappointed, but he's by no means mad; he gets it; he was there for the whole thing.

Although most entrances are excluded from these English-language presentations (a significant limitation, but I am of course grateful to have these files at all, lest I needs get the relevant 海賊盤 / かいぞくばん / kaizokuban [indeed ブートレグ / būtoregu] materials from the basement and play them in one of the two remaining DVD drives in the house [both contained within PlayStations of generations long passed [add them up and we've got a PS5, kids!]), happily the entrances for both guys are included here. And quite rightly, as this is legitimately great stuff: this is about as "into things" as we have heard a 東京ドーム Tōkyō Dōmu crowd so far (wait just a minute: is this maybe the last time they actually run the Tokyo Dome? [okay no, one more time next year, but this is time six of seven! wild!) and everything looks as good it sounds, and it is all just super exciting. At the risk of posting too many low-res screengrabs (as though that had not been our whole deal here since forever):

To the extent to which there is any point to any of this (the broadest "this," one that encompasses our entire endeavour from its beginning right up through to this present moment on a cold but clear December afternoon)—and I wholeheartedly concede there may not be!—Don Frye vs. Hidehiko Yoshida at the Tokyo Dome must be awfully close to it (the point, I mean), it seems to me (to us?). As I listen to Stephen Quadros explain that Yoshida's World Championship title (Birmingham 1999, -90kg) is arguably more impressive than this Olympic gold (Barcelona 1992, -78kg), I am thinking about how, objectively, yeah, the Worlds offers a deeper field, with each top nation sending two athletes per weight category into brackets that have far fewer participants that are there to fill the (super, and, indeed, duper) important continental quotas that help make the Olympics the world's foremost celebration of sport not just for the wealthiest nations but for everybody; this is a huge, huge difference. And yet, when I had the great good fortune to train several sessions over several days with four-time Olympian Keith Morgan in 2008 (we have been revisiting his Georgian grip material all week at the club!), this is something that he talked about a little (though more than I'd expected, certainly): even though your bracket at the Olympics is full of the same people you've been competing with for the last four years, he explained, and you know that last year at Worlds there were twice as many Japanese and French players in your division as there are here (and this is objectively a bad thing for you), the Olympics are still the Olympics, and the pressures are just totally different in his experience (four times over!). The crowd in the hall is one thing, he said, but you look over, and instead of a handful of press, there are endless journalists from all over, and oh man/oh no, there's the CBC; regular people really are going to see this, aren't they? It's just different, in his account, and it is an account I'm inclined to credit. I'm thinking too of a fairly recent interview with Yoshida himself, who, in evaluating the Japanese team's strong performance at the Paris games, took pains to emphasize that the Olympics are just so hard, man; like I know you know they're hard, but they're just *so* hard. His interlocuter was like yeah, but you're an Olympic champion! We all saw it! And Yoshida was like yeah but I went three times and only won once; because it's *so* hard.

To the relief of both Bas and Quadros, Don Frye has removed the 稽古着 / けいこぎ/ keikogi; they are quite certain Frye would have been launched (seems plausible, but who knows?). "Now, without the gi," Quadros thinks, "it's gonna be hell to pay. I'm telling you: Don Frye is one of the most destructive fighters ever in mixed martial arts." It is true, certainly, that in the early(ish) days of the sport, Don Frye's potent admixture of wrestling, boxing, and judo offered evidence of the martial potential of one who had essentially maxed out the reasonably-priced offerings available at the YMCA (it ruled, and everyone loved it because of how hard it ruled). It's worth noting, too, that despite his then-recent kickboxing drubbing at the hands of Jérôme Le Banner, Frye's mixed fighting record stood at fifteen wins against just one loss, and that one loss came in a one-night tournament-final bout against Mark Coleman (like, 1996 Mark Coleman). But this is an older Don Frye, one who has taken quite a pounding over the years, and who has spent a good deal of time "in the shit" generally. Yoshida, four years younger, whose knees are "gone" in the sense that they will not permit continued training at a level that will allow him to compete for a spot on the Japanese national judo team, but really no more "gone" than that, remains just spry enough to drop low for what may at first appear to be the two-handed reap of 双手刈 morote-gari (it is understandably called as such by our friends in the booth [they say a double-leg {same thing}], but what I feel pretty sure was the major inner reap of 大内刈 ouchi-gari all way. You will note that Yoshida initiated this attack before the "ROUND 1" graphic had entirely faded; such is the profundity of his desire to not get clobbered by Don Frye (hey: so say we all):

This particular form of ouchi-gari cannot help but put the contemporary-judo-attuned viewer, I think, in mind of the recent 講道館 Kōdōkan and 全日本柔道連盟 Zen'nihon jūdō renmei / Zenjuren / All-Japan Judo Federation announcement regarding relaxed gripping rules for next spring's openweight All-Japan and Empress Cup tournaments respectively (the short version: one hand gripping below the jacket will warrant neither the caution nor guidance of 指導 shido; the long version is really not that much longer and is really nicely put together [these rules make a great deal of sense of openweight competition, where gripping below the jacket helps level the playing field amongst competitors of greatly differing heights; expect less radical change than this, I think, when the IJF announces its initial guidelines for the next Olympic cycle]). (That was only the second-most interesting post to the Kodokan YouTube account in the last little bit, too; look at this one: 加藤博剛① 「投技」 / KATO Hirotaka① "Nage-waza".)

Anyway, Yoshida has Frye down just a few seconds into the match, is what I am working towards here, and what Yoshida is working towards looks a whole lot like the 袖車絞 sode-guruma-jime / sleeve-wheel choke he made the most of in his strange special-rules match against Royce Gracie (discussed at considerable length here). He has not passed Frye's legs even a little bit, but that's ok for the sode-guruma, a technique that came be known in the Brazilian milieu as the "Ezequiel" after Ezequiel Rodrigues Dutra Paraguassu (I owe many thanks to a Brazilian-Portuguese speaking student for improving my pronunciation of that important name), Yoshida's fellow Barcelona Olympian, who would employ it in the extra rounds of 寝技 newaza he would pick up with willing jiujiteiros. He found some of these jiu-jitsu guys had tough-to-pass guards! So if you are Ezequiel Paraguassu, you just finish sode-guruma-jime from guard; if, however, you find that you are not Ezequiel Paraguassu, I remind my students when this comes up, it really is better to at least half-pass into niju-garami before you try this sort of thing, lest you end up overcommitted and, ultimately, extremely juji-gatame'd. Yoshida doesn't seem to be at any risk of that; nevertheless, he does choose to move to half-guard while keeping with that same 絞め技 shime-waza attack, which Frye doesn't like one bit, and tries to stand. Scramble! Yoshida takes his back, while continuing to threaten a choke, now from the the over/under "seatbelt" arm configuration (so useful—it switches over to juji-gatame almost effortlessly if you are so inclined!); I am going to back the tape up real quick and count how many times Frye's several cornermen (I hear at least two voices) implore him to CONTROL THE HAND (it's good advice): I've got it at twelve, and that's within thirty seconds.

Oh, this is neat: for a few moments, super fleetingly, Yoshida threatens with an 裏三角絞 ura-sanaku-jime, the rear triangle choke—by far the least common triangle in shoot contexts—but the crowd recognizes (or rather anticipates) the threat as soon as Yoshida crosses his ankles, legs encircling the head and arm, though he is nowhere near a finish. The possibility of the technique interests me for its own sake (技 waza is autotelic), but more interesting by far is the audience's recognition, which is weirdly immediate. It may not surprise you to learn that I have a theory! Though this is a vanishingly rare form of triangle to actually finish within actual shoot (as opposed to shoot-style) contexts, it was the kind most commonly seen throughout the entirety of the pre-shoot (though very much shoot-style) portion of The Long UWF: consider, if you will, that the 裏三角 ura-sankaku is the only form of 三角絞 sankaku-jime available in any Fire Pro before 2005's ファイプロ・リターンズ FaiPuro Ritānzu (you will recall it as the PS2 one [you can download it for PlayStation 3 though]). The triangle choke that has come to be foremost in the in the mind of the contemporary martial arts enthusiast broadly is almost certainly the 表 omote, or front-facing triangle choke (which Rolles Gracie claims to have "invented" [his word] after "seeing it in an old judo book," and much sport has been made of this self-evidently contradictory and thus pretty funny claim as a characteristic example of Gracie self-aggrandizement and self-promotional excess, and I too have chuckled over it [a little just now!], but I honestly think we should give a little leeway on this one to a non-native English speaker ["invented," "discovered," "came up with" are all near synonyms with subtly though importantly different implications; I think we should maybe just let this one go?]). As a final point arising from these (actually pretty fascinating?) seven or eight seconds that Yoshida threatens this relatively-obscure-in-real-fighting-but-hypercommon-in-especially-real-fake-fighting technique before grabbing the skirt of his gi and switching his attack to 裾絞 suso-jime (I think "skirt-hem strangle" is probably the best we're going to do on that one), I would like to note that the once shoot-rare (though shoot-style abundant!) 裏三角絞 ura-sankaku-jime has enjoyed something of a renaissance in recent years in the shootmost context of the IJF World Tour: please see example seven from the invaluable Emil Montes' excellent The Art Of Sankaku (12 triangle attacks you should know) for a cutting edge approach that pairs quite naturally with the particular 横三角絞 yoko-sankaku-jime favoured by Ukrainian great/real-life Yawara! A Fashionable Judo Girl!-character Daria Bilodid (a two-time World Champion by eighteen, an Olympic bronze medalist since), which is example nine in the Montes series (for a super traditional, UWF-approved 裏三角 ura-sankaku to really bring this all together, try number ten!).

In time (and honestly not all that much of it), Frye is able to slip out the back, and come up on top into niju-garami / half-guard, where is he held close and tight, as Yoshida does not want to allow any room for striking here at all: he's not looking for a big sweep or escape; he's just like, I think I can hug it out from here. "Ground and pound is one of Don Frye's fortés," Stephen Quadros notes in an understandable hyperforeignism. "Nice, this is good, body shots," is Bas' call, "because obviously judo practitioners don't train those." Can extremely confirm!

After getting all squished up in the corner, our fighters are stop-don't-move'd back to the centre of the ring. "This is under PRIDE rules, folks," Quadros reminds us, "not under some special shenanigans." Light shots lightly fired? Frye has no answer to Yoshida's half-guard, as he is unable to either pass or to strike meaningfully (easy for me to say) from there; emboldened, I think, Yoshida releases his somewhat 足閂 ashi-kannuki'd / leg-bolted configuration, and wiggles the shin and instep of his mat-side (as opposed "guy-side" [sounds weird but a crucial distinction, technically]) leg to Frye's far-side inner thigh and all of a sudden we are in that particular open (or butterfly [or hooks]) guard known to all who gather here certainly as TK GUARD and it occurs to me I have neglected to mention that Tsuyoshi Kohsaka is of course very much in Yoshida's corner on this occasion (as in so many to come). Perhaps you have noticed him in the screengrabs already. Double-underhooks, a lifting action with the shins and insteps right up through the hips . . . this is how you threaten sweeps! That Don Frye has a strong base surprises few, but, unsettled by being "floated" away in that particular way that happens with these attacks, comes right up onto his feet, and leans forward aggressively into and atop Yoshida's guard, looking to strike. It is a rational response, but not without its risks: as soon as Yoshida traps an arm (lefty, in fact), we hear a medium-volume "get out of there" from Frye's corner; "don't let him control the arm." As Yoshida turns his hips, the only comment is "no" a bunch of times, and pretty loud. With the crowd just losing it, Yoshida enters more deeply into his 腕挫十字固 ude-hishigi-juji-gatame attack in the mode most closely associated with Latvian Olympic medalist Aleksandrs Jackēvičs (you always used to see it as the Iatskevich or Yaskevich roll, but now we know it as Jackēvičs). As long-time readers may recall, I think it both rude and gross to put your opponent in a position where they have to decide whether or not they are willing to break your arm in order to win a game, but that's how this one ends; as this is well-trod ground for us, I will not belabour the point further, but merely note it. Great crowd, great match! I loved it! Kohsaka rushes in to join Yoshida in seeing about Frye's wrecked elbow.

"Traditional martial arts, baby," Quadros offers by way of final thoughts. "You can't close the door on the traditional martial arts." Is judo a traditional martial art, or, in its recognition of what John Danaher came to call "the fallacy of deadliness," and judo's (and its derivatives') consequent emphasis on techniques that can be safely trained at-or-near full commitment against resisting partners, is judo the first truly modern martial art? An open question! There is an excellent introductory essay in Renzo Gracie and John Danaher's Mastering Jujitsu that offers compelling analysis along these lines and it is one I recommend (this same volume is the only text I have ever encountered that argues that the north/south position is best understood as a form of side-control [I try to keep myself alive to the weird possibility of this wild notion, but it's sometimes a struggle]).

All that remains of the pride.fc.23.championship.chaos.2.dvdrip.xvid.cd2-kyr.avi file that we are currently enjoying—though it will not be our final bout of the night! there is another! and it is a key one! but it is on a separate file! for reasons that may be interesting to discuss! in a minute!—is a contest between our dauntless comic hero 桜庭 和志 SAKURABA KUZUSHI and Gilles Arsene, a French jiu-jitsu player in his just his second (and what would turn out to be final) professional bout. This is actually somehow the match that went on last, after Yoshida/Don Frye, and the Separate File Fight that awaits us, out of time (more on that so soon; so soon). Baffling! Sakuraba enters this one just three months after his orbital bone was very much broken by Mirko Cro Cop (as discussed here), so I guess the idea was some light work (like it's PWC / it's a cold world / keep that heat under your seat [I know J. Cole is not talking about the heated seats of a late-model Honda Civic in that since-deleted diss track but these are words that nevertheless occur to me when I enjoy mine]). Woah okay, nearly right away, Sakuraba throws like twenty punches, alternating left and rights as though he had figured out Don Flamenco's deal in Mike Tyson's Punch-Out!!, and they are not just unanswered in the sense that Arsene does not punch in return, but like, he doesn't even try to move out of the way of them, really? He just ducks and covers and otherwise does nothing whatsoever about getting punched a whole bunch of times in a row, which seems bad, in that Gilles Arsene is electing to do nothing more than I would do were this happening to me (haha just kidding: I would actually leave). This does not speak well of Arsene's readiness for any of this, nor does it have much to say on behalf of Kazushi Sakuraba's hitting capacities, as Arsene seems largely fine? He sits, inviting Sakuraba to join him in 寝技 newaza. "Sakuraba is primarily a sportsman," Quadros notes. "He's not mean-spirited at all. He's here to win by technique, actually." Our commentators speculate that Sakuraba could finish the match whenever he likes, but is choosing to get some ring time here. I don't know man, this is pretty dry! Even for me! Sakuraba uses some light strikes in hopes of finding openings from 横四方固 yoko-shiho-gatame, but Arsene, grapple-wise, seems no fool. The crowd is utterly silent. "Give him a leglock? Do something?" are Bas Rutten's tentative advices to I think Sakuraba, but it could go either way. The fighters give each other friendly taps as the ten-minute first round ends, and I am huge on friendly little taps to your partner at the end of a round, or to an 受け uke who has helped you develop the shape of your techniques (tap tap thanks so much great job). The same sort of ducked-and-covered, unanswered punching that characterized the earliest part of the first round also opens the second, and the newaza that follows is much as it had been in the first. "Listen, for Sakuraba to come back, he's got to finish this fight," Bas says. "If it's not in this round, he's gotta do it in the third round. If this is gonna go to a decision, that's gonna be very bad for his reputation, I'm telling you." In the end, it does not (go [to a decision]), as Sakuraba finishes an 腕挫十字固 ude-hishigi-juji-gatame that Arsene honestly seemed to simply choose not to defend. What a turkey of a bout! For more on Gilles Arsene, if you are so inclined, you may wish to peruse the CarlCX (friend of the blog!) write-up that accompanies the ファイアープロレスリングワールド / Fire Pro Wrestling World download he heroically created.

What a drag it would be to end our time together with a such a DUD (maybe we were into negative-star territory for a minute there? we might actually have been! in a Sakuraba match, of all things!), and so, how fortunate it is that there remains a further file containing a match that neither aired nor was mentioned even passingly on the English-language broadcast, and yet is so utterly central to our project. That's right: it's 高田 延彦 TAKADA NOBUHIKO, a man so handsome, and so good at pretending to fight somewhat more realistically than many of his contemporaries, that it seemed to the Japanese people that he should try to fight Rickson Gracie for real (twice!), versus 田村潔司 TAMURA KIYOSHI, the central post-Maeda man of our beloved Fighting Network RINGS, possessed of the cold beauty and sylvan arrogance of an elven king, quite possibly the finest in-ring shoot-stylist there has ever been (Volk Han and Tsuyoshi Kohsaka his only rivals [and also pals] in this) in what is to be Takada's retirement match. In a sense, we need not belabour the Long UWFness of what is about to unfold before us, as it is broad blown, as flush as may:

My memory of this bout—and it is a memory I lightly treasure—is that Kiyoshi Tamura, a very fine fighter lately fallen upon hardship, attempts to carry the not-so-hot-at-fighting-for-real Takada the distance for a respectable decision loss to end his senior's career with a measure of dignity, but fails in this, by accidentally knocking him out so profoundly that referee 島田 裕二 Shimada Yūji (he's been with us since RINGS!), however sympathetic he may be to this overall plan, is left with no alternative but to stop the match out of a sense of basic human decency (which, admittedly, has at times eluded Shimada a little, both before this and after); Tamura, as I remember it, falls to his knees, grief-stricken at this shocking and disheartening turn of events. Even if I turn out to mistaken about all of this, and my memory is completely faulty, I will treasure it (the fake memory) nonetheless, and perhaps even more so, because it is such a funny idea, if not thing that actually happened. But maybe that's really how it goes! Let's find out together!

I am pleased to report that, unlike the low-res digitized digital files that have been with us so far this day, our Takada/Tamura bout is clearly low-res digitized VHS, a format we have had just such a lovely time with over the years here at TK SCISSORS: A BLOG OF RINGS. That Tamura enters, impossibly sikkly, to the impossibly sikk strains of "Flame of Mind" is self-evident, but no less impossibly sikk for that self-evidence. To much applause, he bows deeply in each of the four cardinal directions, as is his custom.

The great ovation that greets Takada is on an entirely different level, as is the entire presentation, in what is one of the greatest ring-walks I have ever known just in terms of vibes, vibes that completely overwhelm our knowledge that Nobuhiko Takada, a man of no doubt many virtues, simply cannot fight for real. Doesn't matter one bit.

If you have enough 片仮名 / カタカナ / katakana and 平仮名 / ひらがな / hiragana to read "UWFのジェームズ・ディーン" as "UWF no JAMES DEAN," and to sound out "アイ・アム・プロレスラー" as ai amu puroresura, "I am pro-wrestler," what more could you ever need? There is nothing more for either James Heisig or Duo the owl (R.I.P. to the little tracksuit they won't let him have anymore) to teach you in this regard; go; be free; sound things out a little.

There is of course no way that the match itself could come anywhere close to delivering on the promise of these remarkable entrances, but even accepting that, boy oh boy, it sure doesn't! Not by any conventional measure, that is, or some normative standard of "things that are good." But when, after half a round of fairly tentative kickboxing, Tamura accidently but extremely blasts Takada in the groin with an inner-thigh kick that creeps up a little (some would say too much), an air of debacle begins to settle, and in that way, this is enormously compelling. I can see that my memory of this match was faulty in at least one regard (the first of several? of many?) in that the referee is not the aforementioned Yuji Shimada, but instead Ryōgaku Wada, of whom we are reminded by the SKILL MMA blog: "Wada started his career with UWF International [hey hey!], a shoot-style pro-wrestling organization, eventually moving to Rings [as well we know]. He made the Rings King of Kings rules, as well as ZST's official rules. He's also a personal physical trainer; Akihiro Gono, Eiji Mitsuoka, Hideo Tokoro and Kazuyuki Fujita have trained under him." Neat! Anyway here's the groin kick, the one that has delayed things significantly:

And we're back! That must have been six or seven minutes they gave him to recover (hey man, take your time). The rest of the round is less eventful, but the crowd remains reasonably engaged. Tamura's low-kicks are super sharp and snappy in a way that I certainly recall of Tamura generally (was it Frank Shamrock who said Tamura's kicks were the hardest he'd felt?), but that I had not, in my memory, held associate with this match at all. He is really laying waste to Takada's lead leg, though; the camera zooms in close to show that it has already become a little gross. Legitimate attempt to win the bout? Or a relatively safe way to make things look realer than they might actually be? Ah, it feels like old times around here! After a short exchange of punches, the first in kind of a while, Tamura throws a mid-kick that Takada catches, and pushes Tamura to the mat. Not much action in 寝技 newaza by either player until Tamura's butterfly/hooks/TK GUARD sweep reverses their positions. But still: no striking of note, no submission attempts, and not even any real gesture towards passing. If one's belief is that this match is a work, one complicating factor is that Kiyoshi Tamura's works are all fantastic, and many of Takada's are very good, some great; this, so far, sure isn't (this is not to say that I am not enjoying; I am, on the contrary, enjoying it lots).

Aaaaaaand here it is: a minute into the second round, Tamura connects with a counter right while retreating from Takada's strange charge, and there is absolutely no question that the punch itself and the knockout that resulted were perfectly/horribly real, but, as Tamura kneels tearfully while Takada is attended to, much of this remains a mystery to me.

In surprisingly brief in-ring, post-fight comments, Tamura offers Takada a mixture of thanks and apology, Takada really just thanks, so far as I can tell. Watching this for the first time in ages, this match seemed to me a much straighter affair than it had become in my mind: that it may have been a full-on work (never my position, but a reasonable assumption one might make [or at least a suspicion one might hold] heading into the match (given the participants and the occasion) seems impossible given the finish and honestly just the look and feel and energy of the thing altogether; that it could have been, from Tamura's perspective, a kind of "carry job" gone terribly wrong, seems plausible; but to me, this time around, it felt like a legitimate contest, and Tamura's reaction simply the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings (like a guy said about poems one time), just some serious 先輩 / 後輩 senpai / kōhai stuff working itself out in front of the tens of thousands assembled in the 東京ドーム Tōkyō Dōmu that day, and several decades later, those of us who choose to attend to it here and now. Fittingly, the closing seconds of this crucially lo-res supplemental file see Takada receiving consolation and congratulation from 猪木寛至 Inoki Kanji (later Antonio Inoki, finally Muhammad Hussain Inoki [may Allah be pleased with him)], wrestling's greatest dreamer.

November 4, 2002:

Huge "state of things broadly" piece:

"With its biggest single match since its 1994-96 heyday coming up in just a few weeks, the UFC has received some significant mainstream publicity including extensive articles in both Forbes Magazine and Multi-Channel News this past week.

The 11/22 show from the MGM Grand in Las Vegas headlined by Tito Ortiz, 27,. defending the UFC lightheavyweight title against Ken Shamrock, 39. It kicks off the biggest weekend in the history of MMA in the U.S. Two days later, Pride will have a same-day PPV of its Tokyo Dome show, ironically based around pro wrestling, with the main draw being the retirement of 40-year-old pro wrestling legend Nobuhiko Takada, as he faces Kiyoshi Tamura as a symbolic ending of the UWFI promotion, which was perhaps the hottest promotion in pro wrestling world wide during the 1993-94 down period of the business, and the promotion that spawned two of today’s biggest names in Japanese pro wrestling, Kazushi Sakuraba and Yoshihiro Takayama.

The irony of the pro wrestling tag is that currently both UFC and Pride in the U.S. are trying to run away from pro wrestling, perhaps because of its recent negative appearing taint. On the Pride side, it has gotten so absurd that when Bill Goldberg appeared on the National Stadium PPV, it was actually painful to watch the announcers never mention he was a pro wrestler. It got even sillier when Goldberg was in the ring cutting a promo, in English, about upcoming pro wrestling matches in Japan, and they never acknowledged what he was talking about.

In a recent promotional feature in My DirectTV Magazine on Pride, it said that if you are a fan of boxing, kick boxing, amateur wrestling or martial arts, then you’d love Pride, specifically avoiding mention of pro wrestling, even though pro wrestling is still the most consistent draw on PPV. The vast majority of the Pride audience is comprised of pro wrestling fans in Japan and its biggest draws are pro wrestlers. In the U.S., the hardcore MMA fans (like the hardcore MMA fans in Japan), regularly knock pro wrestling because it isn’t sport. Thus, Pride and UFC, unlike Pride in Japan, have shied away from promoting what is the prime audience that keeps Pride afloat and what was a prime audience in the early days of UFC.

Dana White, who runs the UFC’s parent company, Zuffa, in recent interviews echoed those thoughts, saying that while the pro wrestling audience was one of the main audiences that supported the early days of the so-called freak show UFC (which with no television exceeded 250,000 buys on a couple of occasions in 1995 when WWF and WCW could only do numbers like that for its biggest shows), but that audience wants soap operas. Now, promoting a serious sport instead of a spectacle, they are trying to appeal to the boxing and amateur wrestling audiences. White said they are targeting the “true sports fan,” a bit older and interested in competitive pursuits like boxing, college and Olympic wrestling. In both cases,there is a huge problem with those marketing thoughts.

Amateur wrestling has no mainstream audience. If they can draw every amateur wrestling fan who tuned to ESPN 2 to see Cael Sanderson’s record breaking fourth undefeated NCAA championship end, that would be good for a base 0.2 TV rating. It’s fruitless to target to an audience that really doesn’t exist, as the Real Pro Wrestling backers are no doubt soon to find out. The attempt to go strongly after the amateur wrestling audience, by doing an amateur wrestler vs. submission gimmick and using amateur’s wrestling’s No. 1 icon, Dan Gable, as an announcer and spokesperson, John Peretti’s “Contenders” show on October 11, 1997 drew only 250 fans and only a few thousand on PPV, even though held in Iowa where Gable is one of the all-time sports legends. When the NCAA tourament draws 100,000 buys on PPV (and granted, that is the exception to the rule as the NCAA’s do tremendous live attendance), or a kickboxing event can do that, at least then you are attempting to market to an audience that actually exists in enough numbers that’s it’s significant. Kickboxing is all but dead in the U.S. as a mainstream attraction if it was ever seriously alive, so trying to draw from its tiny audience will hardly make UFC or Pride mainstream. Pride’s attempt to garner the K-1 audience to its live show, while booking three of its biggest stars in Mirko Cro Cop (who was more over to that audience based on his wins over pro wrestlers than his K-1 wins), Ernesto Hoost and Jerome LeBanner at the last big show for crossover proved to be a disappointment. Boxing at the rank-and-file level also has a very limited audience.

What is huge in boxing today are two audiences. There is the general public audience that will pay huge money to see Mike Tyson and Oscar de la Hoya, because they are huge mainstream celebrities. That’s not a boxing audience as much as a celebrity audience, that will watch Tiger Woods even though they won’t watch golf, and who would have watched Michael Jordan even though they wouldn’t watch the NBA years ago. And there is the huge Hispanic audience, mainly in the Southwest, that has expanded so greatly over the past year that some lighter weight fights like the recent Erik Morales vs. Marco Antonio Barrera match drew better on PPV than many recent WWE PPV events. Bob Arum has noted that it’s the Hispanic audience, because of the marketable Hispanic fighters, something UFC doesn’t have, that carries the sport today. The loyal boxing hardcore audience of the past skews dangerously old, even worse than baseball. In theory, the boxing audience should be the prime target cross-over audience, but it’s questionable how much that’s happened in reality. Older fans are very unlikely to change their viewing patterns or open up to a new sport. The new sports that have started gaining a foothold have done so by targeting a younger audience. Even worse, boxing purists are far more critical of UFC than wrestling purists, because it contradicts what they’ve grown up believing–that boxing is the most effective fighting form and a boxer is the toughest man in the world in his weight division. In their mind, UFC maneuvers that aren’t boxing maneuvers are simply wrong, dirty, or barbaric, and stripped away, UFC fighters are simply poorly-skilled boxers. Then again, to a lot of pro wrestling fans, UFC matches are too realistic with physiques and personalities that are too normal and they don’t really want to accept more normal looking people as tougher than the generally more cosmetically designed television stars. Of course, the difference is, the regular pro wrestling weekly television audience and fan base blows away that of boxing.

All new sports have to capture the teenage audience, and few have been successful at it. For all its teenage losses, WWE still does better in that age group than anything except pro football. Targeting pro wrestling isn’t the easy answer or something that on its own will change things greatly, but it’s a far smarter philosophy than targeting the fans of amateur wrestling or kickboxing, sports that don’t even have a regular television presence or one mainstream name. It’s still the only existing audience of any huge size among fans who are young enough to consider trying something new that has any kind of a history of crossing over, even though even that has only been minor in this country because of the nature of the current audience.

Every network that has WWE, as well as WWE itself in marketing ventures outside pro wrestling, has been frustrated at the total inability to be able to market wrestling fans into trying anything else, whether it’s a sitcom on USA, CSI reruns on TNN, the XFL, bodybuilding or WWE sponsored bands that aren’t playing music that WWE wrestlers come to the ring with. If a UFC had existed, it would have been extremely popular with the pro wrestling audience base of the 70s and 80s (one of the most popular questions on talk shows I’d be on during the 80s was “Who would win if it was real between X and Y,” a question that is virtually never asked today because the audience doesn’t care, and also probably recognizes in the current scheme of things how stupid a question it is.

In those days, regional promoters would have had a cow if something like UFC and Pride even existed and would have felt unbelievably threatened by it. Today, it’s a different audience base that is so fragmented today and more of a fad audience than a wrestling audience, which is why it’s disintegrating so quickly and why on the non-WWE level there is less interest in pro wrestling than at any time in modern history.

The Multi-Channel News article said the early owners, Bob Meyrowitz’ SEG, did a disservice because they pushed the extreme violence angle too strongly in promotion. However, without that angle, it also would have never gotten off the ground. Ultimately, what made it so big, threatened to kill it long-term, which is also a statement that may be made five years from now about WWE and can be made today about WCW, and arguably, ECW.

The article credited the purchase of UFC by Zuffa in January 2001 for changing the sport by adding gloves and weight classes, even though weight classes came in during 1997 and gloves were first used in 1995. It said the major breakthrough came in the summer of 2001 when New Jersey and Nevada recognized it as a legitimate sport. Actually, the New Jersey ruling came a year earlier and Meyrowitz promoted his final sellout show in Atlantic City. It mentioned that Vegas casinos are taking bets on the 11/22 show, but that’s also been the case dating back more than one year. What Zuffa did do that SEG was unable to do was get licensed in Nevada, and get on In Demand, and largely save what was a company that almost certainly without new and more professional ownership would have been the third of the major casualties of 2001.

According to both articles, the five shows thus far this year have done between 50,000 and 60,000 buys. White said that two or three networks are in talks with them about a weekly television deal and hoped to have it in place by March of 2003. Fox Sports Net, which aired two Sunday night one-hour specials that drew roughly double what its existing boxing show does in the same time slot, confirmed it was one of the networks’ interested.

The Forbes article focused more on owners Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta, whose Station Casinos company grossed $912 million in 2001, which would be a little more than double that of WWE for a comparison. By owning 26.5% of the company stock, their paper worth in the company is $220 million. In the article, they claim Zuffa is breaking even, which if true, goes against what is being told to fighters and doesn’t seem to make sense when you see production cuts on recent shows and far less advertising for this show than the early Zuffa productions as well as most fighters being dropped from contract when their current deals are expire.

Zuffa’s first major show after some exciting minor ones earlier in the year, took place in September 2001, which saw nearly everything that could possibly go wrong happen on a show (an injury changed the main event, 9/11 took place, a major boxing PPV was moved because of 9/11 to the same weekend as the show, the show turned out to be one of the most lackluster in recent memory and the show didn’t end in the allotted three hours, causing many systems not to show the finish of the main event and causing massive refunds).

In addition, White said the company, which once had 66 fighters under contract, has that number down to 15. The original plans were to lock up a stable of fighters exclusive to the company, to avoid them making stars and having them leave for Japan or an upstart promotion. Now, with the money looking to be down in Japan (and Japan has little interest in paying serious money for anything but light heavies and heavyweights) and no competition happening plus the belief that there have been significant losses that haven’t turned around yet, fighters are being signed on a per-fight deal. This means when someone, like Phil Baroni on the last show, makes a huge impression, they are a free agent.

Their claim is UFC grosses $7.5 million annually, about double what ECW was doing in its final year even though running fewer PPV events per year, minimal merchandise and no house shows (that’s according to the papers in the ECW bankruptcy filing, and I would say I’m skeptical ECW’s revenues were really that low), but a pittance compared to the numbers put on the board by the major pro wrestling groups in the U.S. and Japan which have the many huge revenue streams. Even WCW grossed $120 million in its last fiscal year (although it spent about $185 million that year to do so). The story said the cost of putting on a UFC PPV event is $1.3 million, but at 55,000 buys and Zuffa’s share being $12 per buy, would be $660,000 in average revenue from PPV. Live gates in Las Vegas and Uncasville, CT have been excellent, with five of the past seven shows exceeding $500,000 grosses and the next show expected to go well north of the seven-figure mark. But costs of this show, because of the deals with Shamrock and Ortiz, would also be the highest of any show to date."

and